Appjection - From ‘lawyer’ to ‘superlawyer’: making law accessible for everyone

This case study has been prepared by:

- PhD Fellow Berdien van der Donk

- Legal Research Master Student Willemijn Kornelius

Law must be easy and accessible for everyone. For Appjection, that means that whenever anyone receives a fine from the government, they must be able to appeal the decision easily. Their goal? To build a platform where complicated legal procedures are converted into an easy to use service. The Dutch startup was founded in 2018 by two law students: Max Heck and Matthijs Lagas. The idea to build a platform where users can easily check if their speeding and traffic tickets are justified was the best of many ideas that the duo came up with during a rainy brainstorming evening in a bar in their university hometown Leiden. Flash forward to 2022, they are on the verge of storming Europe.

‘Reading’ and appealing fines as a tool

The service of Appjection helps people to appeal traffic fines which they deem unjust. Appjection provides a platform interface, in which the only thing the customer has to do is press the “appeal”-button and upload a picture of the fine. The tool they developed is an artificial intelligence system. It is based on optical character recognition (OCR) software from Google, a form of text recognition, which uses the picture of the fine to ‘read’ it. The artificial intelligence system is trained to detect the necessary data. The data is then converted into digital text. One type of data the software extracts from the fine is the “fact code” used to define the category of the alleged offense - for example R-602 covers crossing a red light and R-545 concerns a handheld-phone while driving. The tool is trained to generate a set of predefined “yes-or-no"-questions based on the specifics of the fine, e.g. about the circumstances.

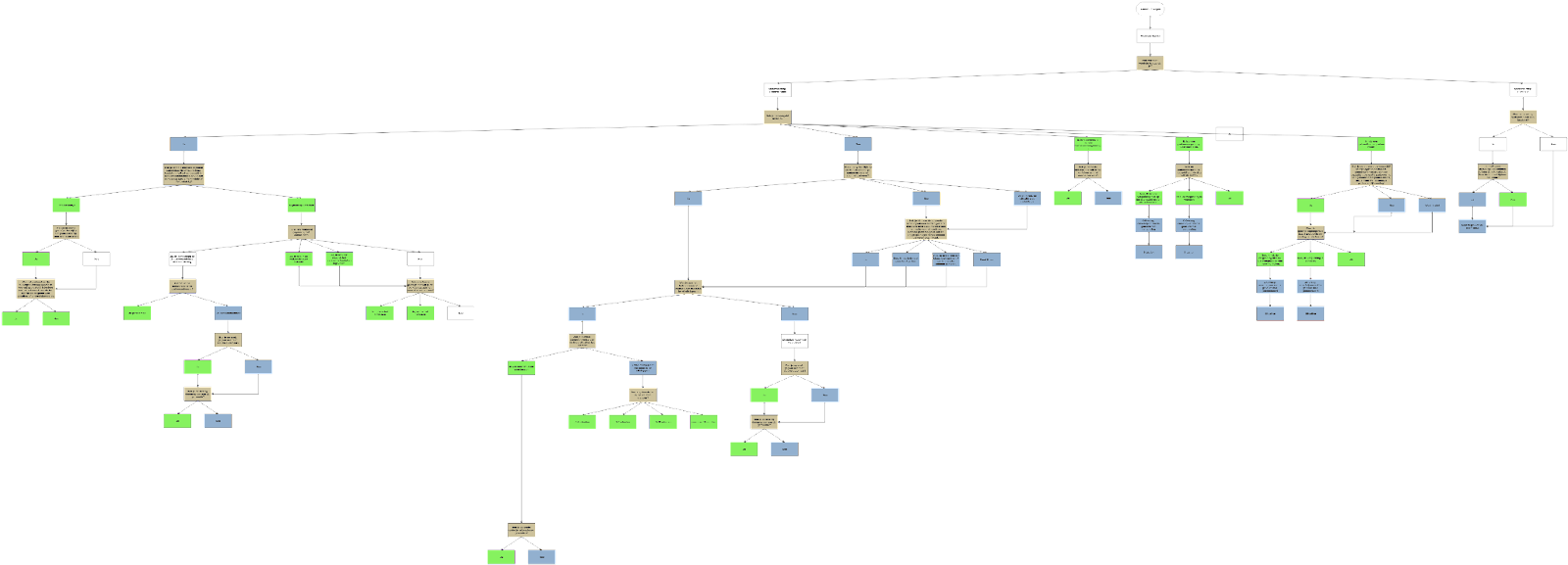

The questions work as a ‘decision-tree’ to determine the success of appeal. The customer answers these questions, which enables the tool to determine whether the fine is indeed unjustified. Subsequently, one of Appjection’s legal employees will review the appeal and decide whether the appeal fulfills the requirements. When no grounds to make a successful objection are found, this is communicated to the customer. On the basis of this assessment, Appjection accepts 75% of the submitted fines. When they do, they take over the appeal procedure and continue with the legal steps. This means that Appjection files the objection with the Public Prosecution Service or with the municipality (depending on the type of the fine). This is all part of what Appjection calls “Phase 1. The intake”. If necessary, they take the objection to the district courts (Phase 2). On the basis of the grounds found by their tool, they are able to generate a notice of appeal. In some cases, they even take the case to the Court of Appeal (Phase 3). From all challenged fines, Appjection’s success rate is around 67%.

Example visualization of the decision tree for a municipal parking ticket

Appjection’s service is free. Dutch law grants compensation for the costs of legal assistance when the fine is imposed resulting from a fault on the part of the government. As such, Appjection receives a litigation fee directly from the Dutch government. The Netherlands thus provided them with a fruitful environment to launch their start-up. However, Appjection is only entitled to the legal assistance fee when the fine is materially unjustified. Currently, only 14% of the submitted fines lead to compensation. Since a large part of the process is automated, their earning model rests almost proportionately on their scale and number of customers: more fines means more compensation, and more compensation means more people get access to justice free of charge.

No pain, no gain: the early years of Appjection

After their brainstorming evening, the idea to actually bring their concept to the market became real when Max and Matthijs participated in the Legal Innovation Challenge of Dutch law firm De Brauw in 2016. As one of three finalists they had three months to work up their innovative idea into an actual business plan with personal help of experts. Afterwards, they presented it to a jury panel. Appjection won both the audience and the jury award, awarding them a prize of €25.000,- and free legal support from De Brauw. Following this first success, Max and Matthijs also won the Gulliver Entrepreneur Challenge of Stichting Gulliver in 2017 worth € 10.000,-. Without this start capital, Appjection would probably not have been around, nor at all in its current form. With the prize money, the founders realized they now had the momentum to make something out of their idea: but how do two law students get from an innovative idea to a working IT-tool? They decided to get on board with Gerrit Jan van Ahee, an engineer willing to develop the necessary software.

The following years were tough: the funding boosted their business, but was just enough to make the necessary investments and did not enable them to earn any money for the first three years. In need of an office, De Brauw offered them a little ‘box’ where they spent their days developing Appjection. During the nights and weekends, Max and Matthijs worked as freelance legal staff for De Brauw so they could earn a living.

From a start-up challenge to a business

The customer interface of Appjection

Right from the start, Appjection managed to establish a collaboration with car leasing company LeasePlan. Max and Matthijs were still finishing their masters, but explored their options to expand Appjection. They reached out on Twitter to the Director of Innovation at legal insurance provider ARAG, who is also the head of ARAG’s incubator The Legal Tech Factory.

ARAG’s CEO put them in touch with LeasePlan. Without an actual product, they managed to convince LeasePlan and set up a pilot. LeasePlan’s feedback and experience with traffic and parking fines enabled Appjection to improve their tool and to prove the necessity of their service for other (leasing)companies. Following the pilot phase, the ‘appeal’-button that directs a customer to the tool of Appjection became integrated in several insurance companies’ and car leasing companies’ services. It also became a part of the (paid version of the) Dutch app Flitsmeister (2.6 million regular users) which warns its users for speed cameras and traffic jams. These companies have customers - regular people taking part in traffic - that form exactly the target of Appjection. The cooperation with these large companies provides Appjection with a big pool of consumers that can easily access their tool, which in turn helps Appjection to increase their profits.

Currently, Appjection has about 55 employees. 35 of them are lawyers or law students working to review the submitted fines, enhancing the software by training it and doing the ‘remaining legal work’. ARAG is still one of Appjection’s biggest collaborators. In 2018, this company announced they would work together with Appjection in the fight against unjustified traffic and parking fines. ARAG, a company with millions of clients worldwide, said that the service perfectly aligns with their aim to continuously look for partnerships to give people an affordable access to justice.

Retaining the lawyer: automation is not always better

Parts of Appjection’s product are completely automated, but Appjection has chosen not to fully automate their service. Statistically, the automated decisions proved equally good as a decision taken by a human employee. However, when implementing this immediate feedback system, the satisfaction of the users decreased. They felt unheard by Appjection - no one had actually looked at their complaint and they were simply denied access to justice by a computer system. Simultaneously, the company’s employees had to be trained to handle the ‘higher-up’ cases that need to be taken to court in person (the more difficult appeals). The most efficient way to teach them was to let them start with reviewing the easier cases.

With their services Appjection allows the ordinary lawyer to turn into a superlawyer. By automating the administrative load that lawyers face in their daily work, more time is left to spend on the client and the actual legal work. In that regard, Appjection’s vision focuses mostly on the automatisation of tedious tasks (physical mail, appeal referrals, automatic reading and processing of fines) rather than the legally heavy considerations that follow from these processes. Whether a fine must be overturned remains up to a physical person: the judge, and the legal research to reach such a decision remains equally - in a large number of cases - up to lawyers.

Struggles of a conservative environment

A big part of their team deals with all the paperwork: as Dutch municipalities and public authorities still communicate through regular mail, they necessarily have to comply with that practice as well. The mail proved a more difficult nut to crack than initially foreseen.

In the early years of Appjection, the company was registered at Max’s home address in Amsterdam. Quickly, the mail started accumulating to a point where tens of letters arrived at his doorstep every day. Since most of the letters were from official instances (courts, fine administrations, etc), he soon became the most interesting address of his mailman, who at one point out of curiosity asked Max what was going on at this address and whether perhaps a high stake criminal was living there. When Appjection moved into their first real office, the problems simply moved place: the mail kept on coming.

The stream of mail caused a big burden on all involved parties. Municipalities and fine registrations would send a physical letter to Appjection, which, in turn, would print the letter, scan it, process it digitally, print it again, and return it physically. Then, the municipality would repeat that exact same process to store a digital copy on their side. Luckily they have now been able to make some agreements with relevant authorities to use digital means to avoid all the double work done, though some (rather conservative) municipalities still stick to the paperwork required by law.

An unexpected new business opportunity: “Fine transfer”

In recent years, Appjection started to look for opportunities to diversify and future-proof their business model and their product. The opportunity presented itself rather coincidentally. Max knew someone working for Felyx, a Dutch shared mobility company. Shared mobility companies like these rent cars or scooters to customers. Felyx struggled with the large stream of traffic and parking fines. As official license plate holders of all the rental vehicles, their customers’ fines are addressed to these companies. It is legally possible to pass on the obligation to pay to the person actually driving the vehicle at the time of the fine, but the legal procedure is burdensome. It also often hinders the client’s legal possibility to appeal the fine. For Appjection, this meant a new business opportunity!

The past years they worked on a new product: ‘Appjection for Business’, which is essentially a “fine transfer”-tool. Through this service, any mobility company can – automatically or manually – upload a received traffic and parking fine and ask it to be transferred to the driver. The tool determines whether the fine can be transferred to the end-user, and if yes, Appjection takes over this legal procedure too. They started out with a pilot to test their tool on a limited amount of fines to see how the administrative authorities and the public prosecutor would react. Eventually, this turned out to be effective and the product was ready to expand to other mobility services, such as Felyx, Check, MyWheels, DriveAmber and GoSharing.

Currently, Appjection works together with a growing number of mobility companies, whom they charge a fee for the delivered service. Compared to the usual costs of these fines for mobility companies, the fee charged by Appjection is negligible. The current focus is on young and innovative companies. These companies are still figuring out the best way to deal with these “legal” problems and are open to technological innovations. Also, the investors behind mobility companies focus primarily on growth, rather than speeding up administrative processes. More traditional mobility companies, such as car rental companies, have often already found their solutions for these problems years ago and do not see a pressing need to change that. Appjection hopes to prove their successes and convince these more conservative parties in the future too.

Scalability and border-crossing business

Max Heck analyses what is crucial for a legal tech startup wishing to scale up: define the problem your product solves and be sure that the company you approach feels the pain of this problem. With the diversification of their product, the opportunity to expand abroad became a reality. The transfer tool is easily scalable. Just as any major city in Europe saw electric scooters pop-up overnight, the rental companies behind them faced the same problems with the transferring of fines to the renter. Since the transfer tool is a B2B paid service, the expansion of this business will allow Appjection to establish a market across Europe. Currently, their service is used in Belgium, France, and Germany. Soon they will expand to Spain and Italy, and they are currently exploring their options in Denmark and Sweden.

Their original product concerning the traffic fines is bound by local administrative rules, which leads to problems when thinking across borders and makes scalability harder. However, that does not mean that Appjection’s aim to increase access to justice stops at the Dutch borders. Quite the contrary, Appjection has taken the challenge to expand also their regular product (appealing fines) across Europe. This has led to some legal challenges. For example, in Germany, fines may only be appealed by registered lawyers, and in Belgium, a court fee of 65 euro has to be paid and, on top of that, a ‘solidarity fine’ of 137.50 euro is due when losing a case. These examples demonstrate how governments are decreasing the access to justice. Offering suitable business models can restore and increase people’s access.

The restrictions make for a tough business case. Additionally, deciding whether Appjection’s service would be viable depends on the penalty amount (which correlates to the willingness to appeal), the possibilities to appeal as a representative, and the total number of fines imposed a year. The legal research into the national rules is carried out in-house. The compensation fee for legal advice, which had formed the foundation for their original product, is not equally available in other European member states. That meant that the business model must be adapted to fit the new markets. In some, insurances for legal expenses cover the costs for Appjection’s services. In other markets, the potential to reclaim costs is still under research. In places where legal aid proves to be too expensive, Appjection could choose to cover the costs with profits from other products to ensure even more people get better access to justice.

Three lessons from Appjection

- What would you do differently?

I would have fully focused on tech from an early stage, because that has turned out to be the core-strength of our company.

- What did you learn from the process?

A lot, but the most important lesson has been that it is impossible not to make any mistakes. Making mistakes is necessary to progress!

- Future thoughts for the legal (tech) industry

Very positive! Since the legal industry is rather conservative, there is a lot of potential for innovation. I do, however, not see legal tech replace lawyers in the near future, rather there are numerous areas where tech could be used to support lawyers.